The Skill Utilization of Gig Workers

With the support of FSC, we are undertaking primary and secondary research to characterize the nature and motivations of the gig workforce in Canada. The research objective is to help inform the collective understanding of and consequently help build toward targeted policy for the Canadian gig workforce.

In 2022 we surveyed 1,000 gig workers in Canada to learn more about their motivations for engaging in gig work and to gain a better understanding of the working conditions and barriers they face. In the survey, we also included the following question: “Are you currently employed in a full-time or part-time salaried job (where you receive a regular paycheck and a T4 for income tax purposes) that is not your gig work job?”. Of the 1,000 individuals surveyed, 695 responded with ‘Yes’.

Of these, 445 indicated that they are employed in a full-time salaried job, 216 stated that they are employed in a part-time salaried job and a total of 34 work both a full-time and a part-time job as a salaried employee.

What interested us in this context is to what extent gig workers may utilize the skills from their salaried employment in their gig work. Put differently, is there a correlation between their salaried job and their gig work in terms of skill requirements? While we do not have data on specific salaried occupations, we do know in which industries salaried gig workers are employed.

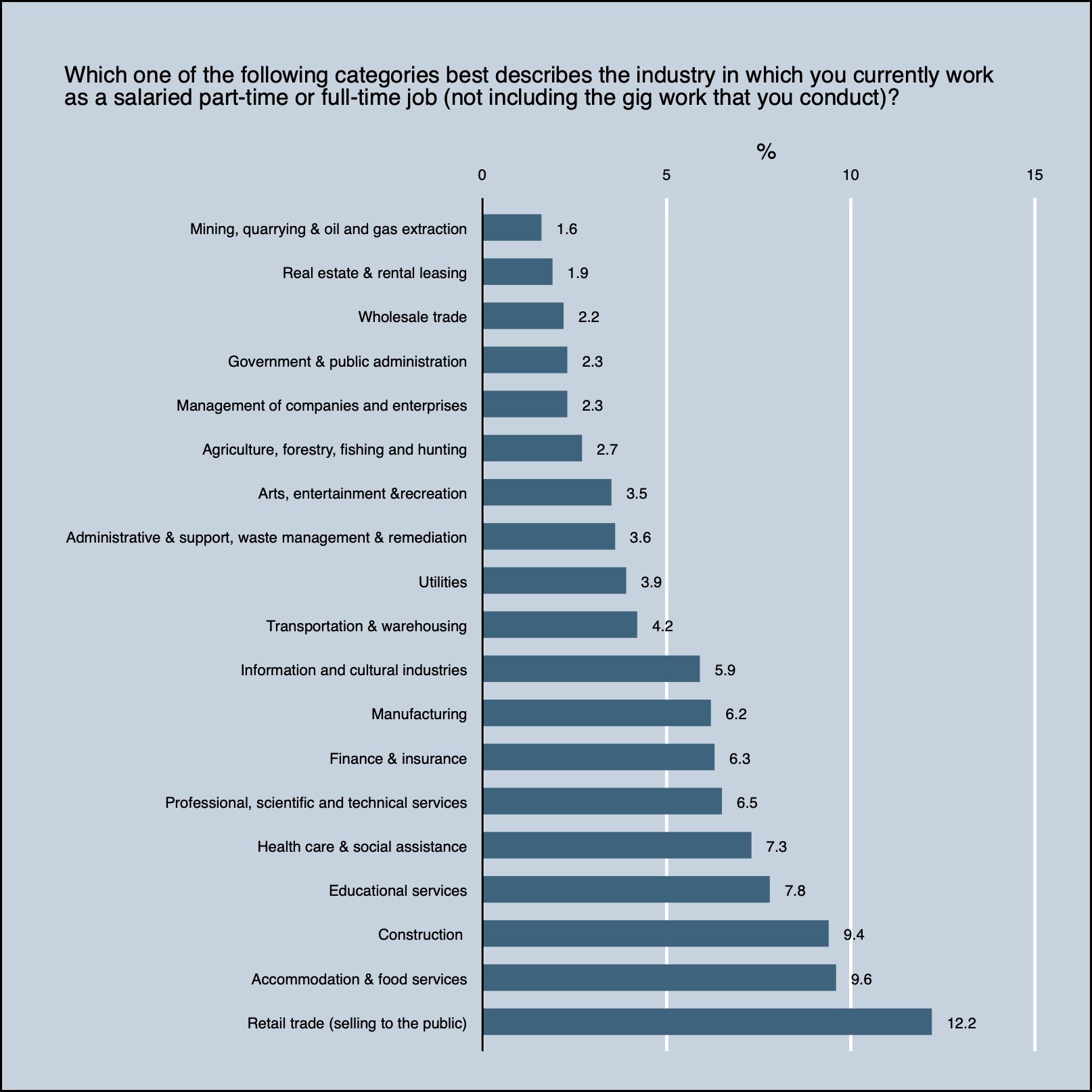

Figure 1 below shows where gig workers who are also in salaried employment work in Canada. As we see, of the roughly 70% of gig workers with salaried employment, around 12% are employed in the retail sector and almost 10% in the hospitality industry. Around 9% are employed in construction, followed by 7.8% in educational services, i.e., teaching and educational support, and 7.3% in health care and social assistance, which includes hospitals, medical offices and social workers. Together these five industries account for roughly 46% of salaried jobs of gig workers in Canada.

Figure 1: Industry employment of gig workers in Canada. (Note: N = 695).

Looking at the numbers in Figure 1, one interesting question is to what extent an individual’s salaried employment may impact their choice of the type of gig work. For example, one could hypothesize that an individual might engage in a type of gig work that requires a similar skill set to their salaried employment as this would lower the opportunity cost of education and training, i.e., the time and resources invested into acquiring new skills or knowledge. As our survey also asked for the type of gig work conducted, we are able to cross-tabulate industries where gig workers have a salaried job, and the type of gig work they conduct.

Figure 2 below depicts an example using the top five industries in which gig workers have salaried job, i.e., retail trade, hospitality, construction, educational services and health care & social assistance. Using a concrete example, we know that around 12% of the 695 gig workers who also have a salaried job work in retail trade.

When looking at the type of gig work conducted however, we see that of those gig workers that have a salaried job in retail (12%), proportionally more of them (25%) engage in ‘music and dance performances’ gig work. Put differently, those gig workers with a salaried job in retail trade are overrepresented in ‘music and dance performances’ gig work. The same is true of babysitting (22%), freelance writing (21.7%), e-commerce (18.9%) and house cleaning (18.4%) for this same group. Similarly, we see that those with a salaried job in accommodation and food services (9.6%) are significantly overrepresented in food delivery (29.4%).

Figure 2: Type of gig work conducted by salaried employees.

Looking at Figure 2, then, what could we infer with regard to potential skills overlap between a person’s salaried employment and the type of gig work they engage in?

Motivations for Gig Work

Several studies on the gig economy explore the reasons for why people engage in gig work. For some it is mainly a way to supplement income while others turn to gig work due to a lack of traditional job opportunities. Yet, empirical findings show that for some gig work is an avenue to pursue their real passion and interests.

As we point out in a previous blog post, a meaningful framework to distinguish between different motivations for engaging in the gig economy has been provided by McKinsey and adapted by the World Economic Forum. They apply the following categories:

• Free agents: In this instance gig work is an individual’s preferred choice and their primary source of income.

• Casual earners: This category refers to those for whom gig work is a personal choice and the resulting income provides supplemental income.

• Reluctants: For this group, gig work is conducted out of necessity and is the primary source of income.

• Financially strapped: This group participates in gig work out of necessity to supplement an insufficient main source of income.

In this framework, free agents are most likely among those who value the flexibility and autonomy of gig work and may choose it to pursue their passions and interests. Reluctants participate in gig work due to a lack of traditional job opportunities which can also include labour market barriers e.g., for racialized Canadians or recent immigrants. Finally, casual earners and financially strapped mainly engage in the gig economy to supplement their income generated in a traditional job. For casual earners this is largely a ‘nice to have’ whereas financially strapped individuals conduct gig work out of necessity to make ends meet.

With regard to skills utilization from one’s main occupation and the type of gig work chosen, we would assume a relatively strong correlation for casual earners and the financially strapped as their main motivation is to earn additional income while keeping opportunity cost low. The rationale for free agents, however, is quite different since they have other reasons for participating in the gig economy. In short, the main motivations for why people do gig work plays a crucial role here.

What Our Results Tell Us

Indeed, our data appears to confirm that skills overlap is just one determinant for the type of gig work chosen by salaried employees. For example, as Figure 2 illustrates, gig workers who also have full-time or part-time salaried jobs in construction, predominantly perform gig work in construction (46%), house repairs (22.2%) and landscaping (18.6%) – arguably areas where skills overlap is relatively high. Similarly, individuals with occupations in educational services, appear to primarily choose gig work where they largely can apply the skills from their salaried jobs. One might also include food delivery (29.4%) and house cleaning (10.5%) for those employed in hospitality and e-commerce (18.9%) for those employed in the retail industry.

Yet, as mentioned earlier we also find that 25% of those engaged in ‘music and dance performances’ have a full-time or part-time job in retail and 12.5% in hospitality. Similarly, almost 22% of those engaged in ‘freelance writing’ have a salaried job in retail. In these instances, individuals likely have a different motivation for engaging in gig work. In other words, the driving factor here might not be to supplement income. Rather, it could be that individuals who hold salaried positions in these industries are pursuing their non-work interests and passions via their gig work.

An interesting picture emerges when we look at salaried employees in health care and social assistance who also participate in gig work. Here it does appear that there is neither a high skills overlap between occupation and type of gig work, nor necessarily a discernible passion. As Figure 2 shows, overall 7.3% of gig workers who also have a salaried job work in health care and social assistance. At the same time, almost 17% of rideshare drivers have a salaried occupation in health care in social assistance. Put differently, gig workers with salaried employment in health care and social assistance are overrepresented in rideshare (16.7%), pet sitting (11.1%) and house cleaning (9.2%). A plausible explanation might be that this group is among the casual earners or the financially strapped, respectively, but there is no readily available gig work with high skills overlap to their professions. Instead, they choose gig work where skill requirements are comparatively low.

Based on these findings, it appears that there is some correlation between an individual's choice of gig work and their motivation for participating in the gig economy. Yet, for those who primarily wish to pursue their passions or non-work interests, the degree of overlap between their salaried occupation and their gig work is of little importance. Conversely, those whose main objective is to earn additional income, either as a casual earner or due to an insufficient salary, would benefit from selecting gig work that has a relatively high degree of skill overlap with their salaried position, as this would keep their opportunity cost low. However, if such work is not available, the next best option is to choose gig work with relatively basic or general skill requirements.

Furthering our understanding of this area could be effectively facilitated by subsequent research specifically tailored to salaried employees who also conduct gig work. This would entail to obtain more specific information on salaried occupations, e.g. through targeted surveys.